Around this time last year I was part of a group chosen by the V&A to design and create a brooch, in response to the up and coming postmodernism exhibition. This premiere exhibition was to be displayed in the V&A from the 24th September- 15th January 2012. My previous post reminded me of this, as a key aspect of the postmodern movement, 1970-1990, was the cutting and pasting of different artistic disciplines. Although the movement is infamously hard to define, it ultimately presented an explosive reaction to the modernist ideals set out by groups such as the Bauhaus. The postmodernists were interested in ambiguity, decoration, intertextuality and mediation '(the reproduction and even selling of things, not just the making of things)'. A principle aspect of the movement was 'historic quotation' refferring to ideas of intertexulaity whereby the postmodern 'author' blends past and current texts. However, this was not intended to construct meaningful statements, they simply found pleasure in seeing how it all fit together. They focused on the surface, the facade, of things and valued concrete experience over abstract principles. However, the movements paradoxical existence is highlighted when their objects become fixed and interpreted, as they simply become another form of modernism. Postmodernism cannot, on its own principles, ultimately justify itself. An essential metaphor of the postmodern movement was the 'Hall of mirrors' as images were bounced from one surface to another, denying the possibility to discern meaning or location.

|

| Left to right: Alessandro Mendini 'Proust chair' 1978; Otto Kunzli 'Brooch' 1983;Wet magazine, April Greiman and Jayme Odgers- No. 20 1979 |

The more I researched this movement, the more confused I became. So I decided to take the starting point, for my brooch, from something that sparked my attention during in the lecture given to us by Glenn Adamson's, co-curator of the exhibition, at the beginning of the project. He explained that the idea of attacking what had come before was the first expression of postmodernism, and was clearly expressed by Alessandro Mendini. Mendini was a radical Italian designer and magazine editor. In 1974 he created a piece called the 'Destruction of the Lassù chair'. This involved the construction and deconstruction of the 'ideal' chair. The very simple chair, a symbol of the perfect object, was placed on the top of a series of steps and set on fire.

|

| Alessandro Mendini 'Destruction of the Lassù chair' 1974 |

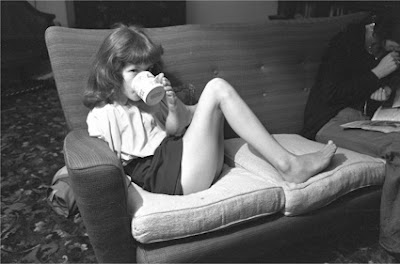

Although this destruction of the 'ideal' effectively announced a new approach to design, I was particularly interested in how the end result existed as an image rather than a product. The image ultimately became the end product, a product that could be quickly and cheaply reproduced.I consequently decided to create photographic brooch that existed purely as an image rather than a 3D object; referencing the postmodern interest in mixing disciplines. I also intended to reference their interests in intertextuality, production, process and facade. I began with a photograph of a previous piece of work I had made, immediately referencing the past. I added a a paperclip attachment to this photograph in order to photograph it as a brooch on someone else. The resultant photograph was then pinned and photographed on someone else. This infinite process of reproduction served to personalise the act of mass production, as the original image becomes more unique as it reproduced. The photographic format of the series also created a piece that simultaneously quotes the past and present in one image. Each photograph in the series was taken of the upper torso, commenting on the increasing formation of 'faceless' connections and the varying facades that exist in our new global society. My brooch ultimately sought to combine postmodern concerns with contemporary society.

|

| The beginning two images from the 'infinitely' long series. Attached to the clothing with a paper clip turned pin. |

|

Developed idea after working with the V&A- Changed attachment: picture hook and self made pin attached to a plastic poster clip coated in gold leaf. The hook references the re-appropriation of objects; the wearer acts as a wall. The gold lead poster clip creates an ephemeral coating that will soon revela the underlying plastic; referencing the temporary state of postmodernism.

Although the impact of postmodernism lost momentum during the 1990's, it is still relevant today as ideas surrounding intertextuality and reproduction are still analysed. This can also be said about the Bauhaus group, which it paradoxically reacted against. The Bauhaus group introduced a new way of working that remains present in art education today. They encouraged the cross contamination of disciplines, and developed an alternative way of viewing materials, colour and form.

I think working closely with other disciplines helps to highlight an question the limitations of each area. During my foundation I specialised in fine art sculpture. I was conscious of creating work that encouraged interaction from the viewer, enticing them to walk round it and become encapsulated by it. The image below is a piece from my final collection, made of aluminium and wood. Although the photo doesn't show the full sculpture, it expresses the merging between sculpture and....jewellery. Questioning the boundary between the two disciplines, if a piece can be worn in some way does that make it jewellery?

|